Vibe Coding vs Guide Coding

I’ve been having a set of very interesting discussions with different people over the past weeks about my experiences with AI coding tools. What I have found in part surprising and in part expected, is that there is a variety of experiences, but many of them have landed on the conclusion of: “It’s a toy, good for prototypes or vibe coders who don’t care about what it produces and don’t understand the mess they are creating” or “I tried it and in our legacy code base it wasn’t effective, I could have done it faster myself”.

End of the day all of these opinions are based on a personal experience that is valid, however I am convinced that it misses the opportunity that exists. We have been given a new and complex tool - a non deterministic one - that doesn’t work like any of the others we have. If you eslint twice you will get the same line of code to fix. If you ask Claude code to solve the same thing twice it can (not necessarily will) give you two different solutions - so this feels very different, and very uncomfortable … but its often when you are finding something uncomfortable that you have the largest room to grow and learn.

So to start this post, I asked Google what it thought Vibe Coding was and it said in its new AI response box:

Vibe coding is a software development approach that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to generate and modify code, where the user focuses on describing desired outcomes in natural language and doesn’t manually write or review the code. Coined by AI researcher Andrej Karpathy, it involves “giving in to the vibes” and letting large language models (LLMs) handle the technical coding details, working by iteratively asking the AI to fix errors or make changes based on feedback until the desired result is achieved. This method is best suited for creating throwaway projects, prototypes, and MVPs, but requires caution and code review for production systems due to potential security vulnerabilities and quality issues.

This completely echoes what I get when I talk to different people in my team and try to show them what I have found is possible using tools like Claude Code, they quickly make two rapid connections: 1 … its vibe coding, thats not for us, 2 … its for throwaway projects, so thats not that valuable.

However I disagree.

Guide Coding

My experience with Claude Code over the past months has been very different than described by Andrej, at no point did I give into the vibes. Instead I decided that I would practice using this new tool - in a methodical and systematic way as I could - to explore what worked, both for my specific use case and the problem at hand. What I have learned is that these tools are indeed very powerful, but you do not get the best out of them by giving into vibes, instead you have to actively and specifically guide them. So I decided to call it Guide Coding.

How does this work?

Important

I will often below refer to a claude.md file, but the reality is this can be a readme, an agents.md or any other file - the important thing is you have something that can be read to provide context in a structured way.

Guard rails & clear boundaries

I have learned that AI tools are no different to humans, they like things to be well documented, consistent, discoverable. They expect things to be where they should be in the code base. If one controller or page has a specific pattern, they expect that pattern to be elsewhere in the code. If it isn’t, they would expect a readme (or claude.md) or a comment to describe why it isn’t. So this does imply that if you had good discipline and quality in your code base before (documentation, good test coverage and high quality tests) that it is much more likely that an AI tool like Claude code would also be effective within your code base.

So the first step you MUST do is invest time and energy in creating guard rails. Adding documentation. Moving things around that perhaps don’t qualify as a refactoring but at least aid discoverability through consistency (naming, location).

- Generate not just one

claude.md, but many - put one in the root folder that helps the AI know how to run the tests, how to start the service, if it should start the service, where the source code is, what the tech stack is. - Then add more - do you have a monolith, add a

claude.mdin the front end code to describe how you build it, do you use React or Vue, how to add new pages, when to break things into separate components, should they be in sub-folders or not, do you use barrel files.

It is somewhat logical on reflection, if you don’t make this investment first then how can you expect anyone, AI or otherwise, to magically discover your architectural intent if you do not describe and document it?

I see too many examples of people giving a task “refactor this” and not investing this time upfront, or putting it all in one huge prompt, and then being surprised when the tool gets lost, confused, or applies patterns or makes stylistic choices you do not expect.

Start with a plan

Claude code now defaults to the approach of ‘Use Opus to plan, then Sonnet to execute’. This works incredibly well, the TL;DR is use it.

I always start with an open and quite clear prompt, for example, imagine that I have a library that allows you to add analytics to an existing transactional database to allow your users to create their own queries / dashboards reports (hypothetically of course).

I discover that I have a major architectural flaw, I have designed it in a way that if a user selects measures from two different cubes, that after joining it suffers from a fan-out. So measures are multiplied by the number of rows of the second table. To solve this you need to carefully construct your SQL queries to pre-aggregate the second table’s data around the join keys, and then join that to the first.

I was able to use Claude Code to effectively make the above refactor in a handful of prompts (somewhere between 10-20), over a period of around 2-3 hours.

The actual commit is here: Comprehensive join system redesign and query planner rewrite.

The way I approached this was as follows:

- First I started a new session (more on this later).

- I start in ‘Opus for planning, sonnet for execution’, now the default.

- I ask it a short and fairly simple prompt, describing the issue I have:

I have a major problem. The current query engine, when it joins multiple cubes together, has a fundamental flaw. It allows cubes to be joined, and then aggregate measures created, that suffer from fan-out - this means that the measures from one cube are multiplied by the number of results in the second. I need to refactor the query planner and query execution stages of the code to ensure that it can a) detect that this has occurred, and b) create a different query to pre-aggregate one of the cubes (not the primary) and then join the result of this to the first. Given all queries are written in Drizzle, this is done by CTE (common table expressions). Can you please carefully review the current implementation, look at what is required to implement this major refactor, and write your recommendations to a markdown file in the docs folder so I can review, and a more junior engineer can execute.

This is of course all supported by the fact that I already have claude.md files in my code base that help it to directly understand the above query - know what the query planner is - and know where to start.

After some crunching it created a version of this file: join-refactor-implementation-plan.md.

At first it wasn’t quite right (and sorry I don’t have the history), but with a combination of adjusting the prompt - e.g. You missed the fact it may be possible for a user to create circular dependencies, please review this part carefully - and direct edits of the file itself, we eventually ended up with the file above. Another good example is the No Backward Compatibility: Clean break from old system to reduce complexity … I had to explicitly add this, as Claude loves adding backwards compatibility even for a brand new module in its first change!

Now, this is where the planning phase ends. And I clear my session /clear.

Clear your session

This at first seems very counter intuitive. It’s just put all this thought into creating the plan! Surely now it has everything it needs to execute! … I have found this is wrong. At this point it seems to have too much context based on all its research and thinking, and if you continue straight away you will hit a compaction event very quickly, and I have found with too much context the quality of what it produces drops.

So, clear your session - this is critical. The plan is written in phases (if it isn’t, ask it to do so). You will clear your session after execution of every phase.

Phased execution

Next is the execution part. So switch from plan mode to edit mode (shift-tab in claude code), and add a simple prompt:

There is a detailed implementation plan for a critical function in /docs/join-refactor-implementation-plan.md. Please read it carefully, and execute phase 1. Before you start please create a branch for this work.

Then it begins. It will begin implementing the changes on a phase by phase basis. So is this where you walk away because this is about Vibe Coding? No, absolutely not.

Guide Coding and the magic of esc

I always maintain a view of the CLI and what it is producing in real time. With my finger hovering over the esc key. As soon as I see it starting to diverge - and this can be scanning files it shouldn’t, thinking about something not relevant, adding code that looks wrong - I quickly hit esc and guide it in a better direction. The file is in /src/server/query-planner.ts. Or I told you not to create test files outside of the test folder.

These interventions should be short, sharp and direct. You are actively steering. I find that after a while I can see when it is on track (and will stay on track), and I then multi-task to do something else. Claude in particular I have found to be very responsive to these types of interventions, don’t hesitate. Also do it if you have forgotten something important you think it may have missed.

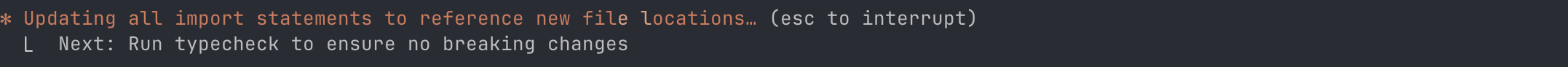

Claude also now has a feature where it shows both what it is working on in your ToDo list, and what it will do next:

This allows you to intervene even before it starts with a quick esc.

It doesn’t always work - but thats ok

Of course it can then get to a point where it will say it has finished, but it isn’t. There is a huge error displaying on the page because it forgot to close a jsx tag, or it has used the wrong import in a file and the server has an error.

Do you expect to get it right first time? I certainly never do. The write > test > fix or red > green > refactor cycle is a core part of how software is written, why is writing software this way any different? So when it fails, that’s ok, we fix it.

In this case, I just paste the error straight in. No context at all. If I see it thinks its finished (you get good at detecting when it is wasting tokens to summarise its nice long completion message!), hit esc - and just paste the error straight into the console. You don’t need anything else.

I have found that it will then quickly find the problem, fix it, and move on. On very rare occasions has it gotten ‘stuck’, and in these scenarios I either intervene directly (I read the code and fix it if it is confused), or switch to Opus and ask it to have a go at it. In all scenarios so far - even some very challenging ones - this combination has eventually gotten to a point we have working code and tests passing.

Phased execution … again

Now you have the first phase done and you are happy with how the code looks, and it “works”. Here is also where if you are not liking the choices re. style or naming, you must give it the prompt here to adjust and also ask it to change the document (or do it yourself) so it has instructions to follow.

Then time for the next steps:

/clear

Then:

There is a detailed implementation plan for a critical function in /docs/join-refactor-implementation-plan.md. Please read it carefully, and execute phase 2.

Then you rinse and repeat. I initially used up time asking it to update the status of the plan in the markdown file, but I have discovered that just asking it to continue phase 2 helps it understand that phase 1 is done (it works), and you can continue this all the way to phase N.

Make it work, make it right, make it fast

This applies fully to AI. I really believe that first you need to (within the guard rails you set above) first let the AI write a working solution to the problem you have defined. Only after this, do you then review what it has done, and decide if it is worth any additions to ‘make it right’. This value question is no different to any other decision you make as an engineer between refactoring and cleaning up a legacy code base vs moving on and building or improving a new feature.

The work you are likely going to want to do here may be anything from more defensive and complete tests (it often needs guidance here), to the fact it built the entire solution with no input validation, or the fact it has hard coded something you want to be configurable based on environment variables or your config library (because you forgot to tell it that part).

This is all OK to change after you have a working version, because I can guarantee that for most new feature development the speed to build that initial working version will be faster than if you had attempted to write it yourself.

I have found this new tool exceptionally good at taking feedback on patterns and consistency (once pointed out) and making incremental improvements or refactoring. So you can do it later, do not expect the output of a prompt to be right first time.

If you look at the Github commit I referenced above, I know you will find a lot of things that from many angles are not yet right:

- The types are really not good and inconsistent.

- There is still some duplication of functions I need to deal with.

- There is still some backward compatibility logic remaining I don’t need.

- I need more test scenarios that stretch different edge cases and possible query scenarios.

For me, I accepted the above, as I was going to work on them all later, and committed it. It worked well enough for now. In another project that is further on you will make different choices, or have better guard rails to avoid it in the first place.

Ship It

Ok, so now you have been through a number of iterations - it is working, you’ve improved the tests, you’ve removed the copy-pasted function it put in 4 places, all of the any types are gone. Is it good enough to ship?

This is where your own experience really matters, but with a new challenge. In a short session you can easily generate via AI thousands of additions / subtractions of code. How do you do a PR of this? Can anyone else realistically review it?

Here is where three things come into play:

- How good are your guard rails? Is it only using existing “golden path” modules? e.g. for auth, for database access. This means you naturally limit the blast radius.

- How good are the types? Did it do a good job adding types (if you have them)? These can give you confidence that the code accurately reflects your domain and intent.

- How good are your tests? Are you confident that this has not broken existing functionality, and the new functionality is sufficiently covered? Do they pass? Has it not skipped any?

- How will you roll it out? I hope you added feature flags or have a way to progressively roll it out in a safe manner?

Important

If you have these safeguards in place, I do not think there is any difference in using AI to help you write code in the way I have described vs asking your average engineering team of mixed skill level software engineers to collaborate and review each others work over a number of weeks to deliver a feature.

In the end you will have a lot of code written that likely you personally have not fully reviewed, and are relying on tests and previously applied guard rails to secure that its behaviour is correct.

I have a thought experiment question:

If this was your first day in a new team, or a new job, and this is the code you inherited and it was live with customers using it and getting value from it. Would you declare it a prototype and throw it away? Or would you apply your experience (using either AI tools or a more direct method) and improve it incrementally?

Are you still with me? Sorry, it’s been a bit long

What’s the take away I want to leave you with …

I think it’s this: agentic coding tools are exactly that, tools. They can be incredibly powerful if used in a guided and pro-active way, by experienced engineers who know what they want and can set good guard rails and intervene when needed. It is especially good on the delivery of new features, both in new and legacy code bases (provided on the latter you abide by my first rule of investing in describing it well first), and needs more support on refactoring poor or legacy code - as humans do, let’s be honest.

The course on Claude Code is an excellent introduction that echoes many of the things I have learned here, I would highly recommend it as a starting point if what I share isn’t sufficient.

I will continue experimenting personally, and exploring ways to increase the knowledge and confidence within my teams of how to use these tools in the most effective way possible. We all talk about 10x, but the reality is that in most large scale engineering teams an improvement of 1.2x (20%) would be transformative in terms of customer value. With this generation of tools, let alone the next generation, this is absolutely possible.

What do you think?